I am more of an aspiring endurance athlete than an accomplished endurance athlete, but I think I know enough about the subject to have some opinions. Firstly, I believe that human physiology, shaped by millennia upon millennia of evolution, is optimized for long-distance running, mostly for tribe-based persistence hunting. Biological evolution is a “use it or lose it” phenomenon, and our species’ ability to cover vast distances at a relatively high rate of speed — more so than any other land-based mammal — is not a gift granted arbitrarily by nature. It is who we are on a fundamental level. And for that reason, despite our relative abundance and comfort in the current age, I believe just about anyone can be trained to run, not just marathon distance events, but far greater.

There are, of course, caveats and asterisks. Despite our physiology being able to support endurance activities, many of us have probably spent a great deal of time sitting at a desk by the time we try to move beyond running a 5K, more so than time spent following caribou across the Eurasian steppe. And let’s be honest, in a world without antibiotics or the other luxuries of science, many of us would not have made it through childhood. I would have probably died before my second year without antibiotics. That all being said, not everyone can be trained to run 30 or 50 or 100 miles without some assistance in this modern age. For myself, as a nearly 50-year-old man, I am putting a lot of time into strength, flexibility, and mobility training. And I am relying upon Hot Yoga and Pilates to do that.

Perhaps if I had adopted this lifestyle at a younger age, the biomechanical issues I am currently correcting would not have required such an attention to detail, and so much planning, but since I was not raised in a paleolithic tribe, I decided I need to do some work on my imbalances, and the consequences of comfort, if I want to consistently run foot races at any distance, or participate in activities like 250-mile gravel bike races. Getting from here to there requires what is, in essence, “project management.” If I want to participate in these events without injury or excessive pain, there is a fair amount of knowledge, in several areas of human physiology and exercise science, required to prepare my body for the rigors of what I am doing a few times per month these days. I need to apply this knowledge in a measured way, over months, to produce my desired outcome.

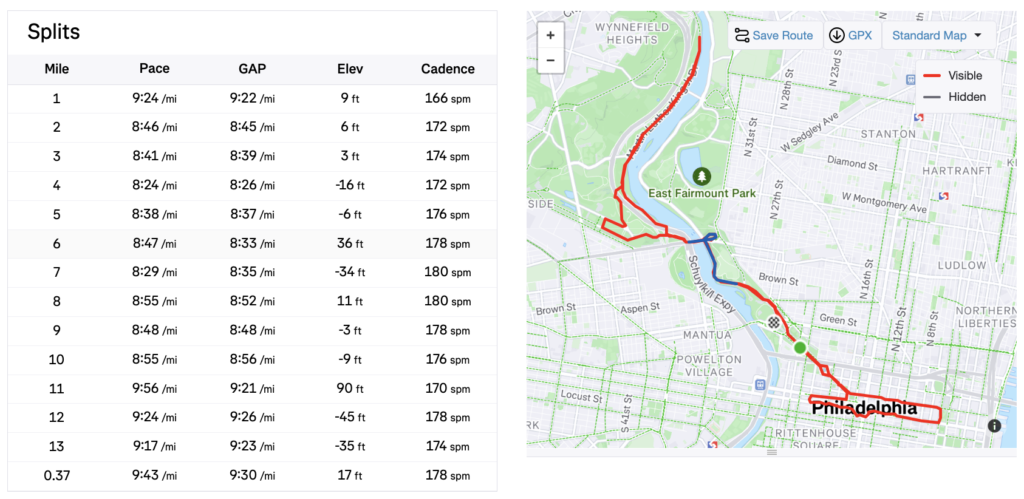

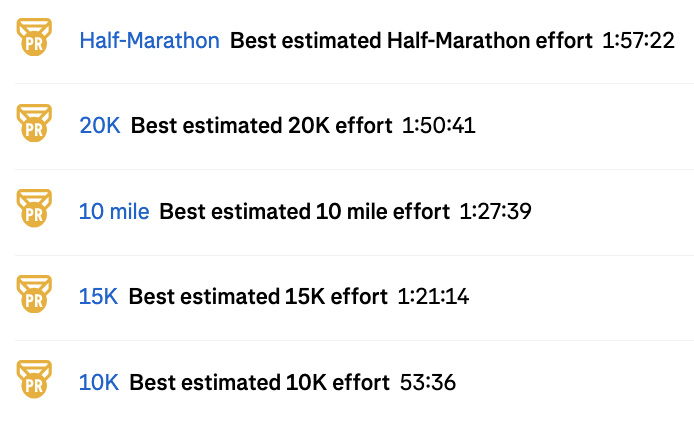

The outcome I sought, for the half-marathon I ran yesterday, was to run as fast I could with nothing more than normal fatigue-induced discomfort. I wished to complete the 13.1 mile distance run on a Sunday, then run a mid-distance run on Wednesday, and a longer run on Friday, just five days later. Although I am not even 24 hours out from the race yesterday, I can tell I will be fine tomorrow. I’m not quite at the point where I could run another half-marathon 48 hours later, but I can put in a solid effort at a shorter distance 72 hours later, and I am happy with that at this point in my training. This is a nice data point to suggest that the knowledge I have applied — the project management aspect of my training — is working. So far. I know I have the cardio basics in place, and I know the human body is capable of what I am attempting, but the project management aspect is key, and I think I passed my first big test yesterday. Not only did I PR yesterday, I can still bend my knees this morning. This is a victory.

The other aspect of endurance training, after project management, is problem-solving. A recurring theme for individuals in endurance events is not so much physical limitations but dealing with issues that inevitably arise during an event. Yes, trying to bike 250 miles or run 100 miles certainly sounds like something that involves physical limitations. But if you did the project management aspect of training correctly, you should know what you can do, and you will hopefully have prepared yourself adequately to do it. But plans tend to be disturbed by reality, and that certainly happened to me this past weekend.

I bought the Germin Fenix 8 about six months ago, and let’s just say, it hasn’t really provided the value a $1,200 price tag would indicate that it should. I don’t know who these people are that keep giving it glowing reviews. When they say they are not being compensated by Germin to write positive reviews, I actually tend to take them for their word. But I don’t know how they have not struggled with the same things that I have, starting with the fact that after you spend $1,200 on the watch, you need to go shell out another $100 for a heart rate monitor that is actually useful. The problems don’t end there. The point of this post isn’t to review the product but to talk about the problem-solving aspect of my race, which Garmin and their over-priced product gave me the opportunity to experience.

The night before a race is always a tough time for me. I spend the entire week beforehand being completely stoked about the experience and also being slightly nervous about whether or not I tapered correctly. Every little twinge I feel in an ankle or a knee is relentlessly analyzed, and I spend many hours before a race trying to convince myself I will be fine. I made it to the night before the race feeling as though I were genuinely prepared. At about the 60-minute mark before I needed to get to sleep, I started my typical Yin Yoga practice, consisting of about 30-40 minutes of long stretches that always help me sleep. I started the Yoga activity on the Germin, and it immediately went into the “blue trinalge of death” loop, which I didn’t even know was a thing. I gave it time to reset, continued stretching, and assumed it would be fine. After a few minutes, it didn’t seem fine at all. One thing led to another, and at about 45 minutes into this technology issue, I had to conclude that it wasn’t going to be fixed before sleep. But I tried one more thing I found online, and it finally stopped looping. Oddly enough, I found the info from some YouTuber — the Geramin website was useless. But I also realized that all of the customized settings I relied on for pacing and real-time estimation of the half-marathon finishing time I was going to need were not going to be available. I planned to try to reset everything in the Uber the next morning. I woke up about 30 minutes before my alarm, but I still managed to get 6 hours of sleep, which is about the bare minimum I need for a half-marathon. This window of time gave me the opportunity I needed to set up everything I would need for pacing. Again. For about the 3rd or 4th time. Because I have had random things happen with this watch that required me to do this in the past. Thanks, Garmin. Perfect timing for a technical issue!

Anyway, I made up my mind that Garmin wasn’t going to ruin this experience for me. I had enough self-awareness to realize that this was the moment of “problem solving” in an event that I was just going to have to contend with. This is why I will bring a paper map and compass on my 250-mile gravel race in September. Depending upon Garmin to navigate or capture/display data you rely on is a very, very bad plan. The idea that people would use this watching for diving borders on unethical, from what I’ve seen of other features. But I digress.

Fast forward to the race. The start command commenced, and I crossed the starting line, knowing the RFID tag on my bib would trigger my clock. So I hit the “Start” button on my running activity… and… the blue triangle of death. Fabulous. BUT THERE WAS A PLAN B. I took maybe 2 or 3 steps, did not panic, and simply started Strava. I should have probably made sure my heart monitor would sync the night before, but that data was not displaying. Great. So all I had in front of me was info on how far I had run. Well, that and the pacer were going to have to be enough.

For the first 10 miles, I felt great. Probably because my training runs were 10 miles. (Recall that I stated I was an aspiring endurance athlete.) But as is often the case, the last few miles are when things get rough. When it comes to these sorts of large, public events, pacing can be pretty problematic for me, and I would assume other people. Back in September, I had some goals in mind for a half-marathon race. I ran the first 2 miles with my corral, and I was absolutely convinced that we were running an 11:30/mile pace. At the start of mile 3, I had given up on my goal, knowing that being that far off my intended pace (9:00/mile) had already sorta of ruined my plans for my target finishing time. I finally took a look at my watch at the start of mile 3 and was surprised to find mile 2 was an 8:04/mile pace, and not 11:30/mile. Conversely, I have been gassed at the end of a race, thinking I was running a 9:00/mile pace, only to find it was closer to 12:00/mile. Like I said, pacing is difficult in these events. And that is why I paid $1,200 for the Garmin watch. So I didn’t have to guess.

Despite all of this, all was pretty well through about the first 10 miles of the race, as I kept my eyes on the pacer to sort everything out. I decided to let him do all of the thinking, which he had suggested we do in a very inspirational speech to the corral before the start. I decided to trust him, enjoy myself, and run the race. The goal was always to not injure myself, and the reality was, Garmin was not going to be able to tell me whether or not it was ok to ignore pain in my right knee. Regardless of what the watch said, that was going to be on me, and my own psychology.

Of course, there was a plot twist: I lost the pacer somewhere around mile 10. I knew that I was feeling well, and the little bit of math I could manage in my head suggested I was on target to hit my finishing time goal or to at least be very close. So now the data I relied on became, “if I feel like I am getting ready to feel like I am about to vomit, slow down a little.” Knowing my body and knowing what an HR of 163 BPM felt like from other runs, I’m pretty confident I finished those last 2 or 3 miles just under my lactate threshold.

In the end, I came across the finish line with a PR that was more than 5 minutes faster than my previous PR set in the fall, and I could bend both my knees the rest of the day. Mission accomplished on both goals. I have never felt this well after a half-marathon, nor finished a half-marathon this quickly. It’s now 13 hours after the starting whistle from yesterday, and I can honestly say I feel great. In the end, I’m going to say I handled both the “project management” and the “problem solving” aspects of this event as well as I could. I know what I can personally do with my body; I know what humans are capable of. And this is really about executive function, psychology, following the plan, and not letting an over-priced paperweight on one’s wrist ruin an experience, nor provide an excuse for injury.

This, in the end, is all prep for the 250-mile bike race. I need to walk away from these “self check-in” events with some sort of lesson learned. The obvious point was made clear: have an analog Plan B for any situation where you are relying on technology. Despite what the marketing tells you or what the influencers say on social media, you need to be prepared to solve problems without a microprocessor strapped to your body. In that moment, plan to throw away the plan. And in a pinch, stopping right before you want to puke might just get you across the finish line in time. That might just be enough.